Celebrating 100 years ago, from the Ottawa Citizen, 21 April 1922.

“Members of St George’s and kindred societies have completed arrangements for the annual celebration in honour of England’s patron saint, St. George. On the evening of St. George’s Day, a service will be held at All Saints Church. Many storekeepers have promised to decorate their premises, and all citizens of English birth or extraction are asked to wear the national flower — the Rose.

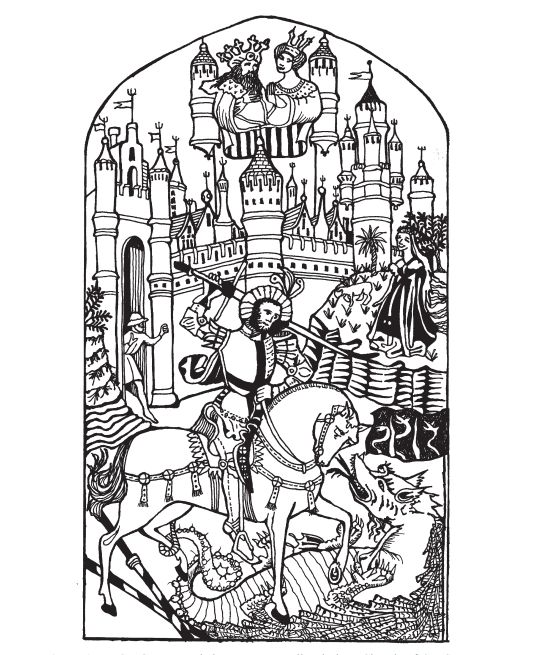

The grand “killing of the dragon” will take place in the Russell Hotel Monday night, when the annual St. George’s dinner will be held. A number of splendid speakers will be heard, and Merrie England will be the theme of many a song and story. St. George’s Society is in a flourishing condition and the membership is steadily increasing.’

Four years later this article by J Sydney Roe was published in the Ottawa Journal. (From the 1912 Ottawa City Directory, James Sydney Roe (1877 – 1942) was Private Secretary to Hon. John D. Reid, Minister of Customs.)

“With the approach of Saint George’s day the thoughts of those of us who were born in England, or whose forebears hailed from there, turn fondly homewards. England is always “home” to the English and that fact does not imply that they do not love Canada, the land of their adoption. Far from it. You will find almost inevitably that an intensified spirit of what may be termed Canadianism accompanies the reverent love that men and women of English birth possess for

This royal throne of kings,

This sceptered isle

This precious stone set in the silver sea.

This blessed plot, this earth,

This realm, this England.”

So it is at this season of the year which brings St. George’s Day the doors of memory fly open and half-forgotten scenes and dear dead faces flash upon the screen. We see the little lanes that wander to the cliffs hard by the sea, the smell of the gorse comes to us again, the whirr of a covey of partridges, the hedgerows with the robins popping around, the fields carpeted with daisies, the woods ablaze with bluebells gently bedecking the graves in country churchyards, the clanging of bells from village spires, the roar of the Strand, the cries of the flower girls at Charing Cross and Piccadilly Circus, and roses, roses, roses! These are the thoughts that crowd in; not of the might and majesty of England, but her simple ways and customs and the friends we knew in the dead days of the long ago. Do you recall the verses about the English spy caught in German lines and sentenced to be shot at dawn?

“ My one regret is England — England the home of man,

All through these hours of darkness I’ve trodden her lanes again,

I can even smell her roses right here in this noisome place, England, my merry England, with the salt spray in her face.”

This is also an occasion upon which one can refer openly to England as England without having some well-meaning person tell you that you should always say Britain. But really you don’t talk about St George and Merrie Britain do you? It is St George and Merrie England. I think it was Chesterton who wrote

“St. George he was for England,

And before he slew the dragon

He took a draft of English ale

From out an English flagon.”

I frankly admit that one is on dangerous ground, very, in referring to so noble a Saint as St George having anything to do with the beverage which, when taken in sufficient volume, is apt to be slightly exhilarating (“Fergie’s foam,” always excepted). So for the benefit of those who are at grips with the demon rum, it is suggested that they change the third line of Chesterton’s poems to “he took a cup of breakfast tea.” That will settle matters nicely, the only difficulty being that in St George’s time tea was undoubtedly as difficult to get as a draft of English ale. But Chesterton’s idea is quite all right. He indicates that St George went about the task of killing the dragon in the orthodox way by having a pint of “arf and arf” before he tackled his job. Eh, what.

Come with me for a moment on a memory trip. This is our day and we honor it. Stand neath the shelter of one of the Landseer lions on Trafalgar Square and watch the surge of traffic sweep down Whitehall, along Cockspur St, up the Strand and Northumberland Avenue. Hear the chime from Saint Martin’s in the Fields hard by. That roar of traffic, the peel of Saint Martins, constitute the sweetest sound in the world of all to the old-time Londoner who visits the city of his birth after long absence.

Come to the Midlands where the Ouse and the Nen meander gently through the meadows, up to Peterborough in the heart of the Fen country with its lordly cathedral; go onto Ely, Lincoln and Norwich, York and Chester. Or if you prefer to go South there is the lovely Kentish country with the hop gardens, Surrey and Sussex, Brighton and Bournemouth, and on to Somerset and Devon in the West. And everywhere we go we shall see the cowslips and roses pass through old-world villages with their Norman churches and “God’s Acre” where the rude forefathers of the hamlet sleep. Lovely verdant England, the land of our youth! We may not notice as many country mansions as we used to remember and we may have to remodel the lines which sang of their glories to

“The stately homes of England,

how beautifully they burn”

And there is lovely Cornwall. I always think of Cornwall as the hand of old England stretching furthest into the Atlantic to welcome home her sons and daughters. Cornwall, wave washed Cornwall where they used to sing:

“And they shall scorn Tre, Pol and Pen

And shall Trelawney die

There’s thirty (sic) thousand Cornishmen

Will know this reason why.”

That, there, our little trip is ended. But can’t you smell the roses, and the sea, my brothers?

I know it’s rather risky just now to talk about the weather when, in these parts particularly, winter has apparently fallen asleep in the lap of spring and does not seem to realize that it is time to go, but I recall the story of the Englishman who landed from a steamer in Montreal on one of those cold rainy days we sometimes get in July. He saw standing on the wharf a man he recognized as a compatriot. “Say matey” he asked, “don’t they ever ‘ave any ‘ot weather out ‘ere, any summer or nothing?” “Blimy don’t arsk me,” was the sad reply, “I’ve only been ‘ere eleven months meself.”

The article continues. To read the rest it’s in the Ottawa Journal of Thursday 22 April 1926, page 6.